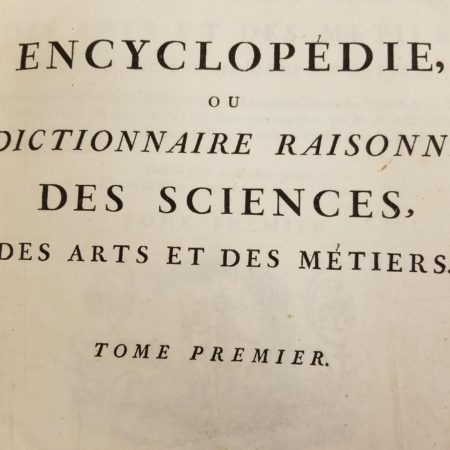

The Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, more commonly known as the Diderot Encyclopedia, not only catalyzed the French Enlightenment by capturing the essence of Enlightenment ideals, galvanizing its supporters, and spreading those ideals to others, but also demonstrates the political machinations that contributed to the movement. Diderot first set out to translate an English two-volume encyclopedia of knowledge, but instead decided to create an encyclopedia that would more comprehensively contain all the knowledge in the world and make that information more accessible to the common people. The resulting Encyclopédie was a bit longer than two books, comprising seventeen volumes of text, including eleven images. Unlike the British encyclopedia, Diderot’s work included a multitude of writers on subjects that went far beyond the arts and sciences; the Encyclopédie was the first of its kind to include information about technology and crafting or trade skills, such as the mechanical arts.

The existence of this twenty-eight volume text stands as a visual testament to the magnitude of the Enlightenment project. Resulting from the contributions of over 150 of the scientists and intellectuals of the French Enlightenment—including Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu, with Diderot as the editor—the Encyclopédie is a momentous collection of human knowledge, created by some of the sharpest minds in history. Indeed, though it was initially so expensive as to be minimally accessible, later print runs allowed its reach to expand, spreading the Enlightenment ideas throughout Europe and beyond. Consideration of the text underscores the Enlightenment philosophy of broad and equal access to all kinds of knowledge, and provides insight into how the Enlightenment radically altered the trajectory of philosophy and, even more broadly, of epistemology.

One of the primary goals of the major Enlightenment thinkers was to undermine the authority of the church and the crown as sole arbiters of knowledge. Not only does the Encyclopédie seek to make knowledge more available to the common people by accumulating it in one collection, easily proliferated through the printing press-it is also strategic in its portrayal of the royal and religious powers. The entry on the king, for example, makes no reference anywhere to divine right to rule, stripping away one of the key foundations on which the royalty had claimed authority.

Perhaps more scandalous was the statement regarding the place of religion in the structure of epistemology. At the beginning of Volume 1 of the Encyclopédie is a chart depicting the categorization of different kinds of knowledge. Two of three major groupings are “Memory,” which includes history and natural history, and “Imagination,” which consists of the arts. The third and largest of the three is “Reason,” situated at the center of the chart and containing everything from mathematics and physics, to logic and ethics. Prominently displayed at the top of the reason column is “the Science of God,” in which religion is placed alongside superstition, divination, and black magic. Even more than the direct shot taken at the authority of the king, then, the Encyclopédie works to undermine religious knowledge, thus discrediting the Church’s claim to authority over knowledge.

These are worthy goals: the spread of knowledge and the recognition of its value, whether it be specific to a certain trade or broader philosophy, has greatly enriched our exploration of the world and the human experience. However, despite Diderot’s attempts to use this new framework of epistemology to undermine the church, his democratic view of knowledge is not in itself antithetical to Christian values. Indeed, the secular philosophers of the Enlightenment had their counterparts in those like Emmanuel Kant, who attempted to reconcile faith with reason. The Christian scriptures also emphasize the importance of seeking truth; the best way to do so is to use all the available tools to examine all the existing information, and to uncover new insights. Enlightenment philosophy played its role in promoting the idea of a division between faith and reason, but did so more as a function of its inherent political agenda than on ideological grounds. More than ideological foes, then, faith and religion were, first and foremost, political opponents.